Why Whistleblowers Should be Wary of AI — TSN Conversations.

Dave Jochnowitz

Partner & Co-Chair of the Outten & Golden’s Whistleblower & Retaliation Practice Group.

Are whistleblowers taking a risk when using generative AI chatbots? Dave Jochnowitz, Partner & Co-Chair of the Whistleblower & Retaliation Practice Group at law firm Outten & Golden, thinks so. TSN’s Sandrine Rastello followed up with him on a blog post he recently devoted to this topic.

What prompted you to write about the use of AI and whistleblowers?

I noticed an increasing number and proportion of clients using AI tools to write everything, from case summaries all the way down to initial emails. Instead of people telling their version of the story and how they feel, what I receive reads pretty consistently like: “I have a high-stakes, confidential whistleblower matter with significant leverage that is going to be a real winner for your firm.”

When I realized AI was writing these initial emails, I started to think about some of the potential legal consequences for these people and the particular dangers that whistleblower clients face when they put their sensitive employment or fraud facts into an AI system.

What are the risks involved? What is the worst-case scenario for whistleblowers?

One risk is the loss of the attorney-client privilege. That privilege is about confidentiality and being able to have a frank discussion with your attorney, opening up about your doubts and concerns. If you run an email to your attorney seeking legal advice through AI, that conversation is shared with a third party and may no longer be confidential.

I don’t know whether unchecking the button that lets an AI system use your prompts to train the model actually prevents AI tools from reusing those prompts. I’m a little bit skeptical that anything you put in there is guaranteed not to stay there in some way.

The worst-case scenario would be for a whistleblower’s identity or allegations to be disclosed and part of their attorney-client privilege lost. Now, everything that they’ve put into the chatbot has to get produced to the company, including things they have said that they really don’t want to be known.

What have we seen so far from courts that worries you?

Until very recently, AI cases have fallen so far into two buckets: litigation against AI companies themselves and litigation about lawyers citing fake cases that AI invented. So far none of them directly impacts what I am concerned about, but they do have implications.

In the first instance, courts are starting to learn that the prompts people put in, and the answers that AI gives back, are recorded. These have become documents, records of communication that exist and can be produced in court, like an email or a letter. Now that you have cases where courts have ordered the production of prompts, the floodgates are potentially open.

In the instance of attorneys using AI to draft briefs and getting in trouble, it is concerning because if courts only see AI making mistakes, they’re going to be suspicious of it. Defendants against whistleblowers could use it to their advantage and say “We think early on, before they had an attorney, this person was using AI and getting bad advice, and we want to know what they were saying to the chat bot.” And a judge might become more skeptical of the whistleblower’s reliance on a tool that has a bad rep in legal circles.

Just this month, we had a third and important development involving AI. A judge in Manhattan held that a defendant could not claim privilege over documents that he sent to his attorneys because he used a non-confidential AI service to write them. So my biggest concern is starting to become a reality.

What parallel can be drawn with the way technology has been used in the past against whistleblowers?

Back when everybody started putting things in email, there was a time when companies weren’t very sophisticated about it. Somebody would send an email saying like “Hey let’s commit some fraud!” and the whistleblower would forward that email from their work account to their personal account, and use that for a whistleblower case. Employers probably had a way to track emails like that, but they weren’t doing it in a systematic, preventative way to prevent leaks of information. That didn’t last.

I think for AI, we’re at the point where defendants might get more aggressive. We’re still trying to figure out where AI fits in the toolbox that lawyers on the company’s side use to get as much information on the whistleblowers as they can.

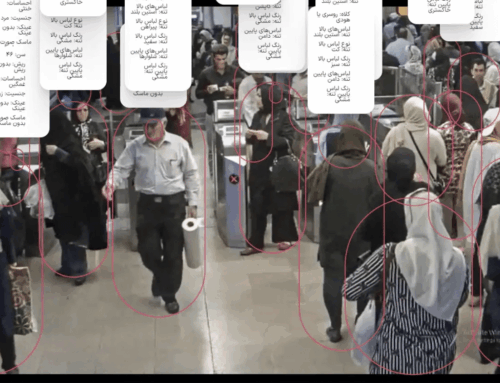

AI technology can also make employee monitoring much easier, going through every single email, every single keystroke logged, every website visited to look for anything suspicious. It is potentially very risky and there is nothing a whistleblower can do about that.

How have you adjusted as a firm to the rise of AI?

We have a client alert that explains the risks of using AI and recommending against it. It is not very helpful to their attorney. Whistleblowers bring something to the table that other people don’t have: insider information, either first-hand experience, which is not AI-generated, or a document that shows that the company did something bad.

If a person is looking for an attorney to expose wrongdoing, the vast majority of lawyers who practice in the whistleblower space will look at their information for free and make an initial assessment. That’s the model.

My recommendation to anybody considering a whistleblower claim is to send it to 15 different whistleblower attorneys. If it’s decent, I bet several of them will at least look at it. If it’s a good claim several will call you back. If it’s not a good claim, you’ll get responses that it is not there. I don’t think AI adds anything to that, other than risk.